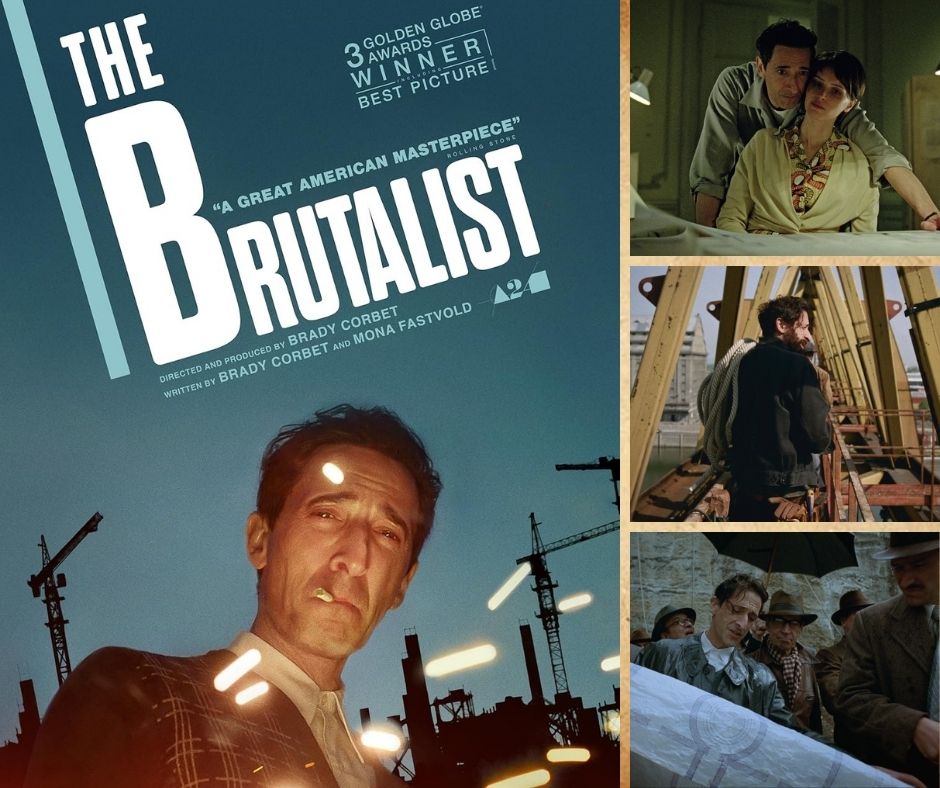

The Brutalist (2024)

There are moments in The Brutalist where it feels less like a 2024 release and more like a rediscovered relic from another era: grand in scope, austere in tone, and unapologetically ambitious. It stands in stark contrast to the fast-paced, maximalist energy that defines much of contemporary cinema. Here is a film that dares to feel monumental, yet remains grounded in emotional detail. It takes its time, slowly evoking the sensation of witnessing real history unfold—convincingly suggesting the passage of decades in one man’s life. So lived-in is its world, and so precise its performances, that—much like TÁR—you might be surprised to learn its central figure isn’t based on a real person. That Brady Corbet achieves all this on a modest, not-even-$10 million budget is astounding. Through period detail, evocative locations, and a challenging yet commanding score, he conjures something worthy of comparison to The Godfather, There Will Be Blood, or Once Upon a Time in America—films that chart a personal journey against the backdrop of a shifting world. That The Brutalist can be mentioned alongside them is perhaps its greatest achievement, even if its uneven narrative may keep it from being remembered quite as clearly.

Corbet’s direction is The Brutalist’s defining strength: confident, composed, and full of bold choices—including being shot in 70mm (a format not used for a full feature since the 1970s) and structured with a 15-minute intermission. The 35-year-old American director, still carrying the sting of Vox Lux’s mixed reception, dispels any doubt about his skill behind the camera within minutes. After a brief overture, we meet László Toth, a Hungarian architect and Holocaust survivor, arriving in America by ship in 1947, while a voiceover reads a letter from the wife he left behind in Europe. In just a few lines, it efficiently establishes the life László escaped, what he endured, and the hope he places in this new beginning. The camera then tilts into an upside-down shot of the Statue of Liberty as László has his first glimpse of America, celebrating a life of new opportunities, while Daniel Blumberg’s main motif forcefully echoes—a sequence so striking that justifies the director eventual Best Director nomination. What follows—a sleek title sequence, a train POV shot, and a heartfelt reunion with a cousin—is edited with mythic precision. In just ten minutes, Corbet establishes the tone and scale of the film and signals that this is a capital-M Movie: the kind of story worth not just watching, but immersing yourself in.

The film’s first half is near masterful. Corbet finds a rhythm that’s deliberate yet propulsive, using minimal dialogue and evocative imagery to guide us through László’s early years in America. The montages are purposeful, the cinematography elegant, and the emotional thread clear. It’s here that Adrien Brody delivers his most nuanced work since The Pianist. His performance—restrained, intelligent, deeply felt—conveys a man gradually rediscovering his sense of purpose. By the time the intermission lands, the film has built remarkable momentum. It’s a structural gamble that pays off. One wishes more films today dared to be this theatrical in presentation (like… Wicked).

The second half, unfortunately, doesn’t quite sustain that momentum. As László becomes increasingly entangled with industrialist Harrison Lee Van Buren (played with stiff predictability by Guy Pearce), the film shifts into more didactic territory. The allegory—about capitalism, artistic compromise, and exploitation—becomes too obvious, culminating in a Venice-set, self-congratulatory sequence where László is celebrated for his life’s work (at the same festival where The Brutalist would eventually premiere—ironically, losing to The Room Next Door). The metaphors, once layered into the visuals and structure, begin to speak louder than the characters themselves and increasingly drive their decisions. This is clearest in a scene involving sexual assault, which attempts to literalize what had already been established thematically. It comes off as clumsy and juvenile in execution, as if the film were shouting, “See? Under capitalism, the master f*cks the worker!”

Despite this, the performances do their best to hold the film together. Brody is excellent throughout—his face remains one of the most striking in modern cinema, and he convincingly communicates intelligence, suffering, and disappointment through subtle movement. Felicity Jones, appearing in the second half as László’s wife Erzsébet, brings poise and strength. She clearly puts thought into every acting choice, though her polished appearance occasionally clashes with the hard-worn reality of her character. Pearce, unfortunately, is boxed into a one-dimensional villain. He’s played this type before (Lawless), and here, the character might have landed better if we had first met him as charismatic or ambiguous, only gradually revealing his true nature. Instead, he’s unlikable from the very first scene—making it hard to believe László would ever trust him in the first place.

The film culminates in a climax that frustrates. After a second act that meanders too long, the final confrontation arrives without the main protagonist present, robbing him of any real resolution to his arc. The wife steps in to resolve the assault subplot, which plays out like a narrative shortcut. The moment isn’t driven by character logic, nor does it carry the thematic weight that the first half seemed to be building toward.

By the end, it’s hard to shake the feeling that Corbet stayed too close to his own real-world frustrations—using the second half as a platform for industry allegory rather than character growth. The result is a film that feels over-sculpted and too controlled, where characters shift behavior to serve ideas rather than emotion. It’s particularly frustrating because these inconsistencies are largely absent in the first half, where Corbet seems more focused on world-building and story.

Even with its imperfections, there’s no denying that The Brutalist is a film of vision, elegance, and scale. The opening sequence, the library recreation, and the intermission build-up are all fantastic moments—reminders of what the film is capable of at its best. Its flaws don’t erase these achievements, and there are still standout performances and sequences scattered throughout the more disorganized second half. It may leave behind a lingering sense of unfulfilled potential, but it remains a rare cinematic event. The Brutalist deserves to be seen, discussed, and—above all—experienced on the biggest screen possible.