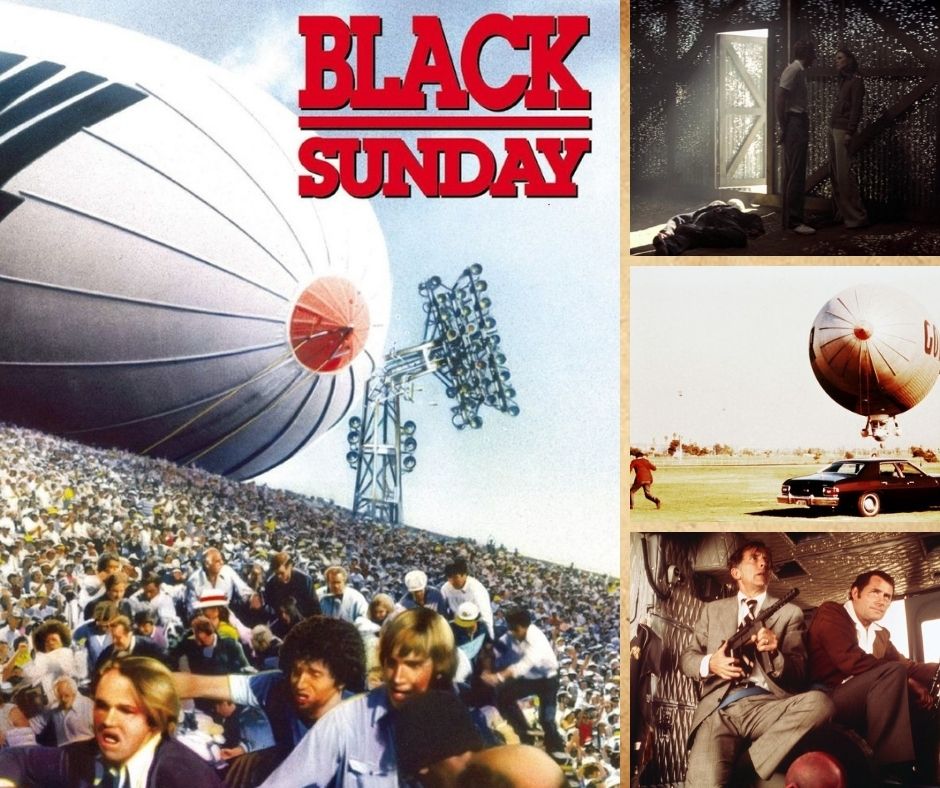

Black Sunday

A Forgotten Thriller That Echoed 9/11

The disaster movie genre was already in decline by the time Black Sunday arrived. Once dominant at the box office with titles like The Poseidon Adventure and The Towering Inferno, the genre had run its course, even with attempts to make it more serious (like 1976’s Two-Minute Warning and Voyage of the Damned). When Black Sunday opened in 1977, few seemed to care. It became a modest success—respectable, but far from a hit—and received no Oscar nominations. Decades later, though, it was rediscovered and often mentioned after 9/11, largely for its eerily accurate foreshadowing of weaponized aviation.

The story follows Michael Lander (Bruce Dern), a Vietnam veteran and former POW, now back in the U.S., nursing a slow, corrosive rage. He’s recruited by Dahlia (Marthe Keller), a member of the Black September organization, to carry out an attack during the Super Bowl. Opposing them is Israeli counterterrorism agent Kabakov (Robert Shaw), who tries to uncover and stop the plot. The film was directed by John Frankenheimer, once at the height of his powers in the 1960s with films like The Manchurian Candidate, but struggling by the mid-70s to find projects that matched his strengths. Black Sunday was a return to form—or at least a reminder of what he could still do when the material gave him room to work.

While the direction is solid, the highlight of the film is the performances—especially from Bruce Dern. At the time, Dern was known mostly as a character actor—an unpredictable presence, not a traditional leading man, but someone who brought volatility and edge to even the smallest roles. Black Sunday gave him one of his most high-profile parts to date, and he responded with a performance that is deeply unnerving. Lander is not a one-dimensional villain; he’s wounded, resentful, and disturbingly plausible. His partnership with Dahlia—coolly played by Keller—feels less ideological than psychological, and the film is efficient in helping the audience understand both. Shaw, in contrast, plays Kabakov as a hardened professional shaped by experience rather than passion, and he doesn’t hide that his actions—done in service of his country—are part of the same cycle of violence. The film smartly puts us in the position of rooting for the most “unlikable” of the three, a man who kills without hesitation in one of his first scenes—making it easier for audiences to instead feel drawn to the two tragic figures.

The film’s first half moves deliberately, and for the most part, it doesn’t deliver the fast-paced thrills audiences might expect from a movie involving bombs and blimps. Instead, it spends time building character, laying out motive, and drawing uncomfortable connections between American foreign policy and the people it leaves behind. There are stretches that feel too long—particularly some of the monologues by Shaw and Dern, which occasionally stall the pacing. But the film finds its footing in the final act, set during the Super Bowl, which delivers strong suspense by blending real crowd footage with sharp editing, detailed sound design, and practical effects. Frankenheimer’s control in these scenes is complete. John Williams’ score is a good representation of the film overall: technically sufficient, never truly bombastic or attention-grabbing, but always adequate. And as a bonus, you get to see what a scene from Mission: Impossible – Fallout might have looked like if it had been shot in 1977.