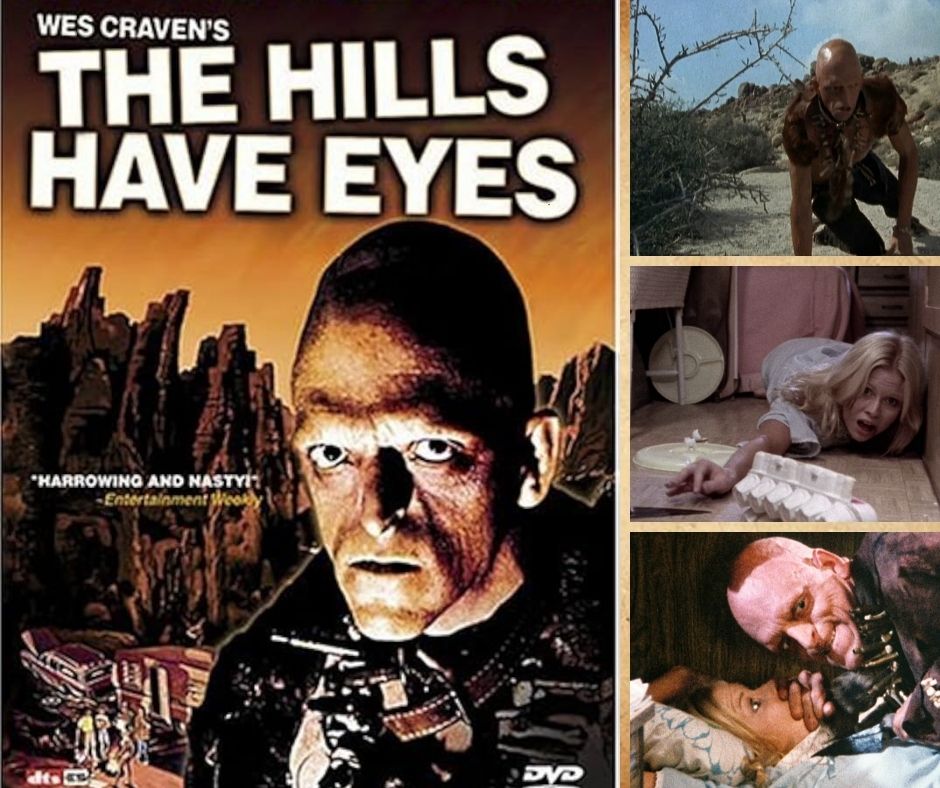

The Hills Have Eyes (1977)

As Unnerving Today as It Was in ’77

Whenever I write a negative review of a low-budget film—like Pins and Needles recently—I usually feel a bit guilty afterward. It’s hard not to recognize the challenges these productions face: limited time, money, equipment, and often experience. You want to give them some grace. But then I watch something like The Hills Have Eyes. Wes Craven’s second film, made in 1977 for just $230,000, cast non-professional actors, relied on natural lighting, and even used recycled clothing to cut costs—yet the result holds your attention from start to finish, crawls under your skin, and stays with you for days. It reminds me that a small budget isn’t an excuse for poor storytelling. The limitations can be frustrating, sure—but they can also spark real creativity.

The Hills Have Eyes is Craven’s follow-up to The Last House on the Left, and it shows a filmmaker still rooted in the rough, transgressive terrain of exploitation cinema while already sharpening his craft. (He would later find huge mainstream success with A Nightmare on Elm Street and Scream, and this film feels like the bridge between his raw provocations and his eventual genre-defining polish.) Inspired by the legend of Sawney Bean—a Scottish clan leader who allegedly led a family of cannibals—Craven reimagines that myth in the American Southwest. A regular family’s camper breaks down in the desert, where they’re hunted by a brutal, inbred family living in the hills.

The film shares one of the great qualities of ’70s horror: the people don’t feel like characters. In the first half especially, there’s an almost documentary feel. What makes this particular film stand out is that we’re following a very ordinary, extended family that includes a baby, two young and inexperienced parents, a grandmother, and two adult children with distinct but grounded personalities. It even takes a bit of effort to piece together how the family is structured, but that only adds to the authenticity. There’s a natural rhythm to their interactions—a lived-in feeling that gives the violence a much greater sense of vulnerability.

Craven builds suspense from the simplest elements: a dog that doesn’t return, the hissing of a radio, or a close-up on a character’s feet as they run over sharp rocks, making you feel like a fall is imminent. There’s smart, effective use of practical effects too: the explosions, the smoke rising from a burned mouth, the unsettling nose-slit makeup, and the now-iconic design of the cannibal clan. But it’s not just the design—the performances from the hill family are disturbing in a completely different register. They feel primal, wired, and dangerous, with just enough twisted logic to make them human. The trailer invasion is the film’s most chilling moment—its tension and claustrophobia are overwhelming. And as the story escalates, Craven keeps it grounded. It never becomes cartoonish or showy. In fact, it’s more balanced than most horror films. By the third act, he even finds room to explore some good themes, drawing parallels between how both families use violence to protect their own.

The Hills Have Eyes didn’t quite become a horror landmark like Halloween, Friday the 13th, or even Craven’s own A Nightmare on Elm Street. It may lack their polish, and it’s not as entertaining—but I’ll take its rawness, its awkward line readings, and its authentically scared performances over something sanitized or overproduced. Its scares haven’t aged a day.