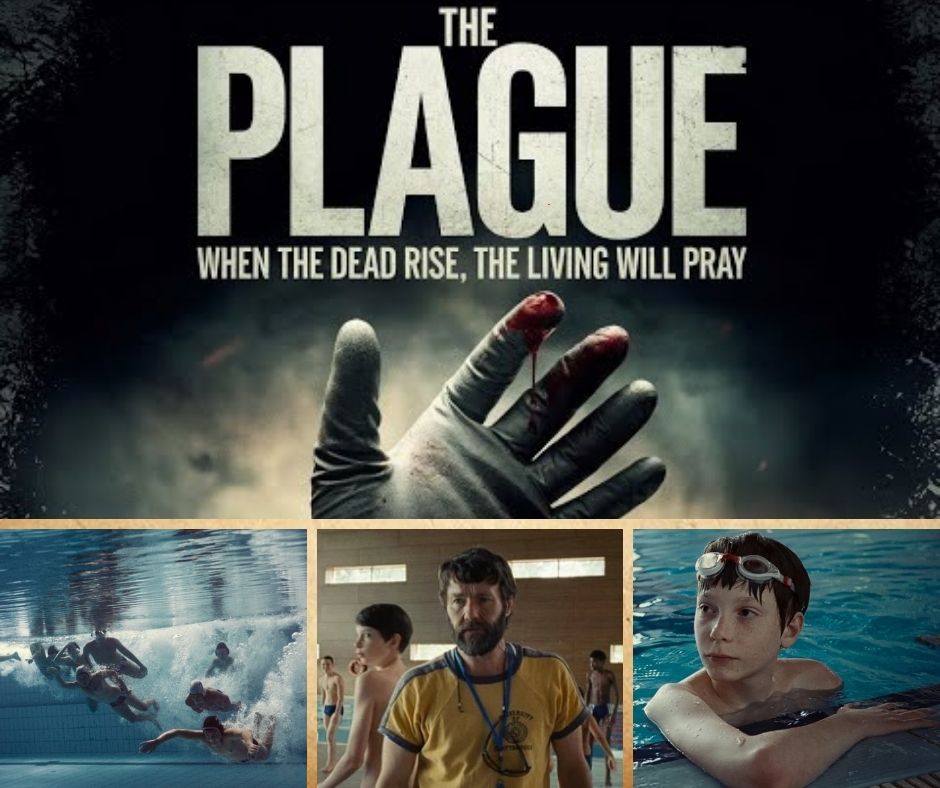

The Plague

Charlie Polinger’s unforgettable debut strips away the sugarcoating of adolescence

In my pre-teen years, I caught the plague—and judging by how painfully authentic his debut feature The Plague feels, so did first-time director Charlie Polinger. Not a literal illness, but something quieter and more insidious. It spreads through whispers, side glances, and silence. It feels like being marked, excluded, made untouchable. Polinger captures that experience with striking clarity, stripping away the usual nostalgia and warmth that often define coming-of-age stories and replacing them with something far more honest: terror. The terror of being left out. Of being mocked. Ridiculed in public. That awful, sinking feeling when the few people you’ve trusted suddenly turn their backs on you.

That’s eventually what happens to 12-year-old Ben (Everett Blunck), a new kid sent to a summer water polo camp in 2003. He’s not an outcast at first—smart, socially aware, trying to fit in—but also not quite popular. He can’t pronounce the final “t” in “Boston,” which makes him an easy target. Still, it’s nothing compared to Eli (Kenny Rasmussen), a quiet, isolated boy with a skin condition the others cruelly nickname “the plague.” When Ben begins to show empathy toward Eli, he starts slipping down the social ladder—forced to choose between going along with the cruelty or becoming its next victim.

Polinger directs it all with surreal intensity and a sharp eye for mood and detail. The camera lingers just long enough on moments of casual cruelty, letting us feel the complicity of those who stand by. Some underwater scenes are stunning and otherworldly. There are flashes of horror, too—brief, jarring sights of blood or injury that hit like panic attacks. It’s all heightened by Johan Lenox’s haunting, glitchy score, which scrapes at the nerves and mirrors the confusion and dread building inside Ben. The tone may feel strange at first, but it perfectly matches that time in life when everything starts to matter and nothing feels safe.

The performances are remarkable across the board. Blunck gives Ben depth and convincingly captures his growing frustration. Kayo Martin’s Jake, the camp’s unofficial leader, is effortlessly charismatic—never cartoonishly cruel, and even hints at hidden insecurities, particularly when talking about his brothers. Eli is perhaps the film’s most moving character, and Rasmussen brings real weight to his silence and awkwardness. Joel Edgerton plays Daddy Wags, the camp’s coach—the familiar adult figure in this kind of story. He brings warmth and a lived-in quality to the role, even if he feels deliberately peripheral. The adults here are present, but disconnected from the real emotional battleground.

The Plague captures the early 2000s without cheap nostalgia. There are era-appropriate songs, sure, but it never leans into sentimentality. There’s no internet, no phones—just raw, face-to-face social pressure. Watching it brought me back to that time in the worst way, reminding me how deeply subtle bullying can cut, how easily a stray comment can damage a kid’s self-worth, and how early we learn to hide parts of ourselves just to survive.

By the end, I wasn’t just shaken—I felt recognized. The Plague isn’t just a great debut; it’s one of the most painfully accurate portrayals of adolescence I’ve seen. It hits you in the places you forgot still hurt.