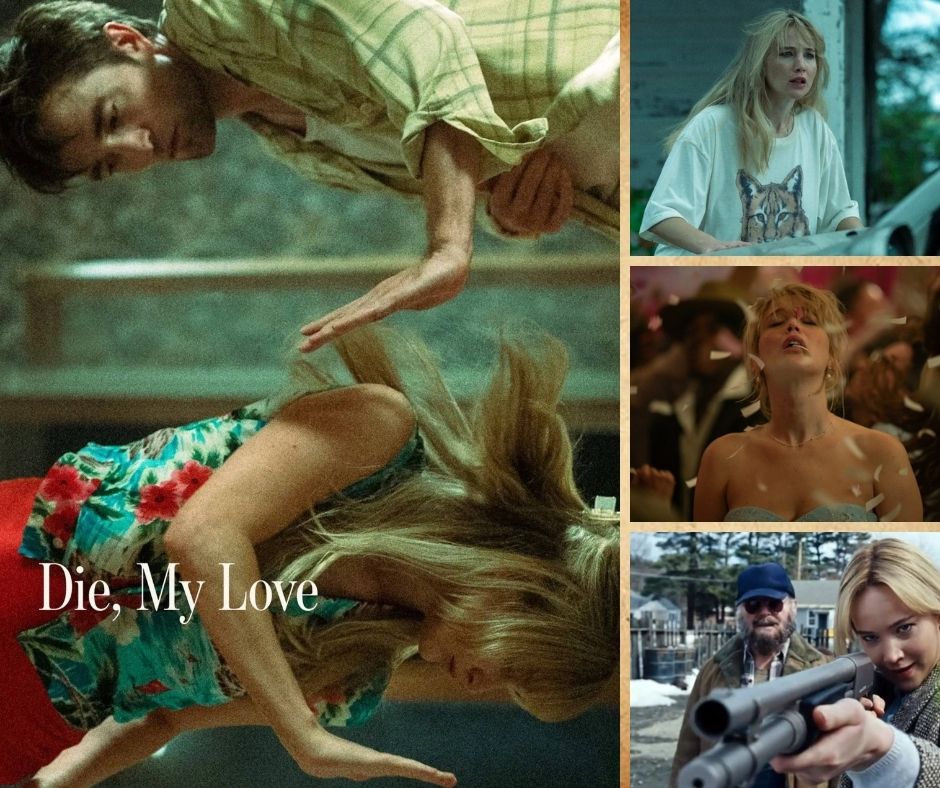

Die, My Love

Motherhood Is Tedious

It all starts quietly—a couple moving into a house they’ve inherited after a relative’s suicide, brushing off dust and dancing like they’ve got all the time in the world. And for a moment, it feels like they do. But since this is a Lynne Ramsay film, that comfort doesn’t last. The event that shifts everything: the protagonist becomes a mother.

From then on, the abundance of time turns cruel. Days stretch endlessly, silence becomes unbearable. Unlike last year’s Nightbitch, which treated motherhood as a disruption of peace, Die, My Love sees it as too much peace—until it curdles into boredom. The protagonist detaches—from her baby, her passions, and her husband, who seems to have lost all desire for her. It’s no longer a relationship, just proximity—she’s raising a child next to a man who’s become little more than background noise.

Ramsay does strong work placing us inside her head. She makes excellent use of sound design, turning the domestic space into something almost hostile—mosquito buzzes, car engines, and the baby’s cries become almost unbearable. We also feel the weight of repetition, the dull ache of waiting for something—anything—to shake her awake. Even a visit to her cruel mother-in-law feels like a break in the monotony. We’re completely on her side when it comes to her husband and his circle of quietly judgmental friends. We’re drawn so close to her unraveling that it’s hard not to root for it.

The film often slips into surreal territory—visions, dreams, fractured memories that blur the line between reality and imagination. But Ramsay never lets it go fully abstract. There’s always control, always a slight distance. It’s a fascinating tension, though it sometimes holds the film back from diving deeper into her breakdown.

Not holding back is Jennifer Lawrence, who completely disappears into the role. She brings the same ferocity she had in mother!, making her character’s unraveling feel raw and inevitable. Her frustration centers on Robert Pattinson’s distant husband, a role he plays well, though the script renders his coldness a bit too one-note—even if there are hints of deeper layers. There’s some ambiguity around what’s driving his detachment (homosexuality is suggested but never confirmed), but a less one-dimensional presence might have brought more complexity to their dynamic. As it stands, the film paints him as such a despicable figure—abandoning her on their wedding day, no less—that it makes the source of her pain almost too easy to define. Just dump this guy!

There are moments where the film comes alive—an outburst at a party that recalls Charlize Theron in Young Adult or Tully feels electric. A wedding scene builds toward something bold but then frustratingly fizzles out. By the final stretch, the film begins to spin in circles, never quite reaching the emotional release it seems to be building toward. It ends on a series of striking images that feels too ambiguous to resonate, too inconclusive to satisfy.

Lawrence is phenomenal, but the film drifts. At times, it’s so withdrawn it ends up mirroring the very emptiness it’s trying to explore.